By Jan Sierhuis*

It was a telling moment after Jermaine Reid** finished his presentation to the 26th Annual General Meeting of the Port Management Association of the Caribbean (PMAC) in Antigua (June 28, 2023). The international maritime lawyer took his audience through a formidable list of challenges facing Eastern Caribbean ports, and addressed the need to collaborate and adhere to international maritime standards.

Among the challenges he addressed were regulatory pressures and an outdated tariff system which he said does not generate the necessary revenue to pay for port investments required in the 21st Century.

The expected reaction came from one in the audience: “So you are proposing a raise in regional port fees?” Mr. Reid concurred.

Current tariffs do not generate sufficient revenues for key investments. Trade volumes in the Eastern Caribbean are generally low and rate increases have a strong negative economic impact. Physical space for improvement in most ports is limited or otherwise requires substantial capital investment. And because they are publicly owned and unionised, port labour costs are not controlled by the ports. Export is close to non-existent, and import growth rates are determined by external developments (read tourism). Most Eastern Caribbean ports therefore operate with low volumes of trade in a high-cost business environment. How then will Caribbean ports overcome the challenges raised by Reid, and collaborate successfully to implement international standards?

The only available option it seems is greater efficiency in port operations. And this requires support from both government and port stakeholders. Even then, to make it socially and politically acceptable, change must be supported by programmes aimed at softening the socio-economic impacts. Local funding for such programmes may not be available. And so, port managers have only two choices: seek outside funding, or look locally for private investors.

Financing efficiency

Public funding is available from multilateral institutions, including the European Union (EU), the World Bank, and the Caribbean Development Bank (CDB) et al. The process, however, takes much time and requires long-term government support. Private investors, on the other hand, will insist on sustainable business plans, which will usually include government guarantees to secure investments over time. In some cases, overseas partners or suppliers may provide funding in exchange for property rights and/or long-term contracts. How governments deal with this differs from one country to the next. Actual trade volumes and growth opportunities can generate investments and tourism seems to be a change agent in the Eastern Caribbean.

The bigger picture

A bird’s eye view of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) economies and ports helps to put issues into perspective. Caribbean economies, until the 1980s, were dominated by agriculture bulk trades. The ports servicing agricultural hinterlands were conveniently located in the towns along the coasts. Some bigger island states (depending on distance, mountainous terrain, and then-existing road systems) had more ports serving agriculture.

Most OECD container terminals date back to the 1980s/1990s when agriculture and bulk trade were gradually replaced by tourism and container trade. Tourists flock to the towns and seaside resorts, not in the agricultural hinterland, thus completely changing the internal transport and logistics landscape. In the 21st Century, tourism led to overdependence and ports thus found out what that meant during the financial crisis of 2008, and more recently during the coronavirus pandemic. However, tourism in Caribbean states has proven resilient and since 2022, growth levels have been slowly getting back to pre-COVID-19 days, with cargo import levels again rising. Some port performance constraints are also resurfacing.

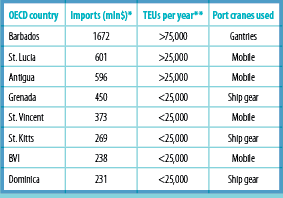

Table 1:

An overview of selected OECD countries/ports for which recent data were available.

A clear picture emerges from these data. When imports value more than USD500 million, container throughput levels start exceeding 25,000 TEUs per year. This seems to be the threshold for using portside cranes, instead of ship gear, BVI and St. Vincent being the exceptions. (This may be related to their status as yachting destinations, where faster port handling is critical for attracting more customers). For gantries to be used, twenty-foot equivalent unit or TEU levels of more than 75,000 are needed. Barbados clearly is the regional small-island powerhouse in this sense, driven by its tourism.

OECD ports are publicly owned and operated, although some (e.g., Barbados) have placed port assets in state-owned private companies. This is explained by higher volumes creating pressure to use more space; expensive port equipment and labour.

Port efficiency – Back to basics

With property, equipment, labour, volumes and growth levels being given, where and how can regional port managers improve their local port’s performance?

To understand the basics of port performance, it is useful to conceptualise port operations as an intermodal transport model, where container boxes are moved from ship to truck and vice versa via an intermodal transport operation, using infrastructure, equipment, labour and monitoring systems (see Diagram 1).

Port inventory

Seaside, ship gear or quayside ship-to-shore (STS) cranes load boxes off the vessel. They go on moving horizontal vehicles to the yard, where they are stacked with rail-mounted gantry or rubber tyre gantry cranes, reach stackers and forklifts. They move according to destination (import/expert/transhipment), status (full/not full/empty) and/or content (perishable/non-perishable).

From the yard, the box is loaded with yard gantries onto a truck and weighed at the gate coming in and going out. Export boxes are handled in reverse.

Each transport mode requires dedicated cranes, vehicles, trained staff, and monitoring systems. The exact layout and logistics involved with each operation can be, more or less, optimal. Much depends on available space, volumes during peak hours, available cranes and vehicles, as well as trained crane and vehicle operators.

Key performance indicators

For port terminals, measuring key performance indicators or KPIs to manage operational efficiencies and productivity is crucial. This is done at the quay, in the yard, and at the gate (see Table 2). The throughput determines how fast containers need to be handled. The vessel needs to depart in a given time period, and has to be offloaded/loaded during this time.

The throughput on the quay is usually measured by TEUs during ship operation.

The length of the quay and number and type of crane determine the speed at which STS operations take place. Ship gear moves boxes slowly (<10 moves/hour), mobile cranes are faster (10 to 20 moves/hr), and gantries are even faster (>20 moves/hr). Faster means higher capital investment and operational costs. The inventory optimum is determined by available space, throughput and number of peak operations in a given period. The time a container spends in the yard indicates the yard’s performance, and is usually referred to as “dwell time”.

Finally, the number of trucks moving in and out of the gate indicates the efficiency of gate operations.